1988

Chicago Institute for Architecture & Urbanism (CIAU)

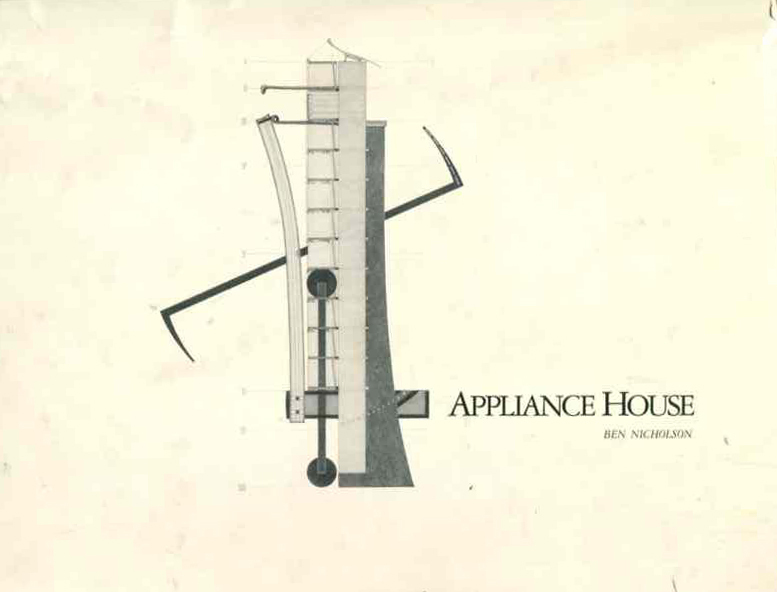

Appliance House

The Appliance House is a unique four-year project that shifts the mildly incredible into something that is difficult to discount.

The Appliance House is a unique four-year project that shifts the mildly incredible into something that is difficult to discount.

Ben Nicholson

There is a man who lives on the street of London and each week he visits St. Martin’s crypt on Trafalgar Square to eat and talk. He relates how he knows Queen Elizabeth very well and that they do many things together. When asked how he came to know her, and whether she was in fact the Queen of England, he answered that he knew she was the Queen because she showed him where she kept the crown. It was placed on top of the wardrobe in her bedroom, he said. The story told by this man has had a profound effect upon the rationale behind the making of the Appliance House. For his tale has become the benchmark of the house’s credibility. The story nudges the poetic, but somehow falls just short of conviction. It is the hollow substantiation that lingers beyond the storyteller’s first hunch that makes the story falter.

The Appliance House is a project that shifts the mildly incredible into something that is difficult to discount. By assembling frail and barely recognizable traits of urban existence into firm gestures, the Appliance House is formed into a Sub-Urban Home. Anonymous mundane details of livelihood are rescued from careless anonymity by successive coaxing and polishing. Hunches about the Appliance House and its components are given names. These names are then reinforced by drawing and collage to permit the proposal to abandon the realm of shadowed idiocy that haunts an initial idea. The idiot shadow, and the figure that throws it, are fused into a single entity capable of shedding its form to reveal a house.

Once the intention of making a house has been confirmed, the conditions of everyday life are investigated. The pervasiveness of mechanical objects and appliances that apparently nurture homeliness are taken at face value. To make a house, a house for appliances, it makes sense to absorb pictures and images of fridges, can openers, and bread tags. Two fat catalogs were chosen as the raw material for the synthesis of an appliance and a suburban home: the Sears Catalog and the Sweets Catalog. The American institution for store bought articles and the encyclopedic collection of brochures aimed at the building industry were delved into, cut up, reconstituted, and congenitally united with the help of the collage’s knife. The resultant collages are then ordained with names and house parts.

Giving a drawing a name that is not necessarily, nor even typically, associated with the things depicted in it can be jarring. Yet the act of naming is a kind of ordination and helps to make the unfamiliar thing or event seem more familiar and more plausible. By calling something an object it can be somewhat tamed. For example, when a collage is named “Side Panel of Appliance House,” the collage (made of scraps of paper) can be considered a representation of a wall, however difficult it may be to believe. Once the hunches, catalyzed by the collages, have been given names, they are then spurred on to be confirmed by drawing and building.

Face name collage. © Ben Nicholson.

Sagittal name collage. © Ben Nicholson.

Sectional name collage. © Ben Nicholson.

Call the Appliance House a Sub-Urban Home turned into a shelter from every kind of consumptive adversity the city is able to muster. The house is simply composed of three parts of small rooms facing onto a hall whose doors to the street and garden are pierced at either end. Each room encloses an accentuated state of normal, everyday, suburban living, living, but the rooms have all changed their ceramic nameplates. Where there used to be the cozy nook with an open fireplace, there is a furnace to suit the pyromaniac within us all. Where there was once a study, in which the Toby Jug collection and family sports trophies were displayed, there now exists the Kleptoman Cell, a room given over to the face-to-face confrontation of what it means to have in one’s possession any object gleaned by any means, fair or foul. These worded descriptions mark the point in time when given names are assigned to the component of the house. They are not yet substantiated by any structure that can make the collection of names any more viable than the frailty of their written form. It now remains for this moment to be catalyzed.

Maquette. © Ben Nicholson.

Maquette. © Ben Nicholson.

Full-scale construction. © Ben Nicholson.

Telamon collages in sections. © Ben Nicholson.

Telamon collages in sections. © Ben Nicholson.

Interior and exterior elevations of cell wall and flank wall. © Ben Nicholson.

Flank wall interior and exterior elevations. © Ben Nicholson.

The Pin. © Ben Nicholson.

Nicholson, Ben. Appliance House. Chicago, IL: Chicago Institute for Architecture and Urbanism, 1990.

Ben Nicholson’s work reflects the concerns of a generation educated and influenced by Daniel Libeskind and John Hejduk but establishes a highly individual search for rigor, precision, and craftsmanship in architecture. Here he analyzes the structure and form of everyday objects such as appliances and bread tags to construct the theoretical and physical framework for an Appliance House, a shelter from Sub-Urban life, a receptacle for all the forgotten objects of society. This book brings together numerous sketches, pencil drawings, color collages, and models that provide a detailed account of this unique four-year project.

Ben Nicholson

was educated at the Architectural Association (AA) in London, the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, New York, and Cranbrook Academy of Art, Michigan, and was Associate Professor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC). He has guest taught at the Southern California Institute of Architecture (SCI-Arc) and the universities of Edinburgh, London, Michigan, Houston, and Cornell. Publications include Appliance House (MIT Press, 1990) and Thinking the Unthinkable House (Renaissance Society, 1997). He has exhibited at Foundation Cartier, the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA), Whitney Museum of American Art, and the Venice Biennale. His interests range from agriculture to gun culture, and primitive geometry to labyrinths. He is currently coediting a book entitled Forms of Spirituality: Architecture & Landscape in New Harmony, as well as The World: Who Got It?, the companion volume to his 2002 satire The World, Who Wants it? (Black Dog Press).