The purpose of this article is to better understand the political content of the now ubiquitous term, sustainable development. Perhaps the most elegant definition of sustainable development yet devised is that by planner Scott Campbell. His definition is illustrated by a simple equilateral triangle in which the competing demands of the three e’s—environmental protection, economic development, and social equity—occupy the triangle’s corners. The three e’s have been conceptually related by a public discourse associated with the environmental movement over the past thirty years. What is novel about Campbell’s contribution to this discourse is the triangulated structure of the three variables and his proposal that correspondingly, a series of three rational conflicts occupy the triangle’s sides. Campbell’s point is that sustainable development lies at the geometric center of the triangle and can be achieved only by negotiating and thus balancing the dynamic conflicts that naturally exist between the networks of interest nested in each corner. [1]

Although Campbell’s definition is extremely helpful, we will argue that it does not go quite far enough. Implicit in Campbell’s logic is the idea that sustainable development is a discursive mode of conflict resolution. Such an activity, we argue, is inherently democratic because it assumes that citizens in conflict will rationally resolve their disputes in public space. To further develop this hypothesis, we rely on the description of Strong Democracy developed by the political philosopher, Benjamin Barber. [2] Barber argues that the history of Western liberal democracy is constituted of three dispositions—anarchism, realism, and minimalism. In this political taxonomy, each liberal disposition distinguishes itself by opting for alternative modes of conflict resolution: anarchists tend to deny the existence of conflict, realists tend to suppress it, and minimalists tend to tolerate it. This distinction will be further developed below.

Introduction

Our specific goal in this investigation is to relate Barber’s categories of liberal democracy to Campbell’s discursive model of sustainability. In a longer format we intend to investigate all three dispositions through case studies of three cities that exemplify each historical tradition—Austin, Texas as a case of liberal anarchism; Curitiba, Brazil as a case of liberal realism; and Frankfurt, Germany as a case of liberal minimalism. Each of these cities employs the rhetoric of sustainable development, but they do so with very different political objectives in mind. This article, however, will be limited to an empirical test of Frankfurt as a case of liberal minimalism. We will argue that the City of Frankfurt, and more specifically the Commerzbank tower constructed there between 1993 and 1997, is a case where liberal minimalists have attempted sustainable development. This project, designed by Sir Norman Foster and Partners, has been well publicized as an example of sustainable urban architecture.

The immediate investigation is in four parts. In part one, we lay out Campbell’s definition and modify it according to Barber’s theory of Strong Democracy. In part two, we investigate the general history of the banking industry in Frankfurt, and in part three we investigate the particular development of the Commerzbank tower. Finally, in part four, we consider a pair of symmetrical questions. First, does the triangular model of sustainable development accurately describe the development of Frankfurt and the Commerzbank tower? And second, do the development of Frankfurt and the Commerzbank tower provide evidence that will help to renovate the theoretical model of sustainable development?

Part 1: The Theoretical Model

In Campbell’s construction the concept of sustainability is inscribed within a triangle of three competing interests—those of economy, ecology, and equity, or the three e’s. Campbell’s worldview implicitly accepts the notion that, in a society as complex and diverse as our own, conflict between rational parties occurs naturally. The Development Conflict, for example, sets those with an interest in protecting the environment against those with an interest in the just distribution of available resources. Thus, on this side of the triangle, Deep Ecologists for example, who value the spiritual or aesthetic content of the undisturbed forest over human interests, would naturally come into conflict with labor unions who promote the employment opportunities of forest workers. Likewise, the Property Conflict sets those who control the means of production against those with an interest in distributive justice. Thus, on this side of the triangle, corporate and business interests in search of reduced production costs will naturally come into conflict with working people who need a healthy living wage and wish to avoid their neighborhoods becoming environmental sinks for industrial waste. And finally, the Resource Conflict sets those with an interest in economic development against those with an interest in resource conservation. On this side of the triangle, industrialists in search of evermore scarce raw materials will naturally come into conflict with ecologists and sportspeople who wish to maintain the integrity of natural systems. In this triangulated model, the sustainable city is one that best balances, or achieves a state of dynamic equilibrium that relates all three sets of competing interests. The emphasis here is on the construction of fluid relationships between competing interests, not upon simple mathematically negotiated settlements.

Campbell makes it very clear that professional planners, and presumably architects, have both an opportunity and a responsibility to serve as principal actors in the mediation of conflicting urban interests. [3] In our view, this characterization qualifies the triangulated model of sustainable development as a political philosophy. We make this argument based upon one made by Benjamin Barber. Barber’s approach to political philosophy is relational, not epistemological. We mean by this that Barber is interested in plans for collective action rather than abstract conceptions of truth. In other words, he is—like the philosophers Charles Pierce, William James, and John Dewey—more concerned with practices than with ideas. [4] In his pragmatist view, the ultimate political problem is not deciding what is good, or what is true, but deciding what we are going to do. [5] In similar fashion, the triangulated model of sustainability does not illustrate the variables of truth. Rather, it implies an activity of balancing dynamic forces. It is the discursive and pragmatic quality of the balancing act Campbell proposes that characterizes his triangulated model as inherently democratic. Extending Campbell’s model in this direction, however, requires giving the term “democratic” better definition.

According to Barber, the tradition of liberal democracy that derives from Locke, Hume, Bentham, Mill, and other Enlightenment philosophers is constituted of the three “dispositions” mentioned above: anarchist, realist, and minimalist. [6] All three dispositions are simultaneously present in the Western form of democracy, and all three are conceived as responses to the kind of inevitable social conflict articulated in Campbell’s model. However, each disposition differs in the nature of its response to social conflict. This suggests that differing political regimes tend to gravitate toward one or the other of the modes of conflict resolution depending upon their attitude toward the individual citizen. To reiterate, Barber categorizes liberal anarchists as “conflict-defying,” liberal realists as “conflict-suppressing,” and liberal minimalists as “conflict-tolerating.” If we accept Barber’s categories for the moment, it suggests that Campbell’s triangulated model of sustainable development is a classic example of liberal-minimalist political philosophy because it rests upon a foundation of tolerance for social conflict. [7]

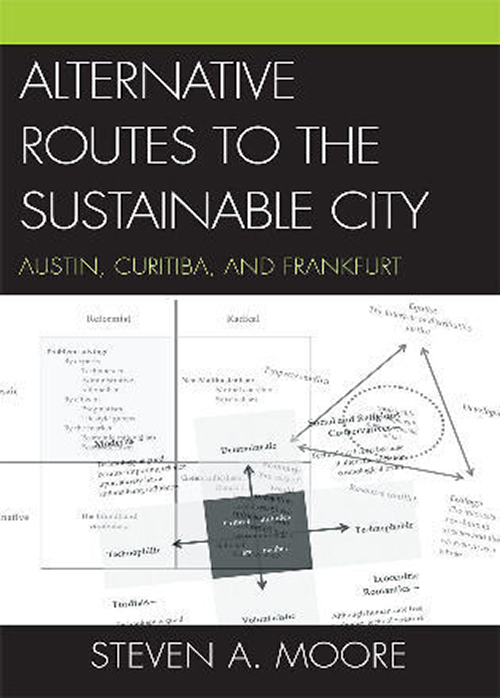

In Barber’s implicit hierarchy of political philosophies, liberal minimalism gets closest to a coherent plan of action—closer than either liberal anarchism or liberal realism—but ultimately falls short. Liberal minimalism is unsatisfying for Barber because it fails to challenge Lockean assumptions that describe citizens as nothing more than “atoms of self-interest.” [8] Barber’s proposal for Strong Democracy—which he introduces as a fourth historical possibility—is critical of this reductive or atomistic view of citizenship. In Barber’s view, liberal minimalists envision polity as nothing more than the representation of private interests in public space. Barber, however, has in mind a far more complex and rewarding kind of “public talk” that describes citizens as participants in a collective project. This is an ontological rather than an instrumental position. A goal of this investigation, then, is to test the triangulated model of sustainable development proposed by Campbell to determine if it can apply the values of Strong Democracy to the problem of urban development. As a starting point, all four historical dispositions of liberal democracy are characterized. The structure is clearly teleological in that it suggests history will progress from the left to the right of the page—toward the condition of strong democracy. This is, of course, the authors’ hope, not an inevitable historical outcome. Although the anarchist and realist dispositions of liberal democracy are given equal space in this matrix, the terms that describe those traditions will not be further developed here. Rather, we will investigate the liberal-minimalist tradition in Frankfurt using Campbell’s triangular model of sustainable development to determine the city’s potential to realize Barber’s proposal for Strong Democracy. This investigation will, of course, require a historical view.

Part 2: On Tolerance and Banking in Frankfurt

The modern history of Frankfurt’s banking industry begins, according to popular accounts, with the narrow defeat of the city’s nomination to become the capital of the new West German nation. [9] It seems that West Germany’s first Chancellor, Konrad Adenauer, favored Bonn as a temporary capital, rather than Frankfurt as a permanent one. The loss of this distinction was particularly painful to Frankfurters because the city has had a long association with the German aspiration to nationhood. In fact, until the Holy Roman Empire of the Germanic Nation ceased to exist in 1806, 33 of Germany’s 52 kings and emperors were elected within the city’s walls. In 1240 Frankfurt was granted imperial protection as a trade center and in 1382 it officially became a free imperial city—meaning that the burghers of Frankfurt answered directly to the emperor. In more recent history Frankfurt was the capital of the German Federation from 1816 to 1866 and in 1848–49 the Paulskirche in Frankfurt hosted the emergent nation’s first democratically elected parliament. The post-World War II rejection of this distinguished political history, popular accounts claim, stimulated the imagination of citizens to fabricate an alternative, or consolation identity for the city—that of the nation’s financial capital. If we cannot become the nation’s capital, this logic argues, we will become its bank.

Secondary evidence lends credibility to this popular interpretation of Frankfurt’s modern transformation. On the 18th and 22nd of March 1944 much of the historic center of Frankfurt was destroyed by Allied bombing raids. This tragically cleared ground became a prime development opportunity in the postwar city. What would have been declared to be a historically significant, and thus protected stock of half-timbered medieval houses, became instead a development opportunity. Add to this situation Frankfurt’s central geographic location in Europe, its hub airport and railway network, and the postwar decision to move the German banking industry from Düsseldorf appears only rational. This popular account of Frankfurt’s modern history is promoted by such mainstream publications as Der Spiegel [10] and was relayed to the authors by, among others, the environmental activist Jürgen Braune and the Commerzbank executive Arnheim Müller. [11]

This interpretation of Frankfurt’s apparently resilient history, however, neglects uncomfortable information. The discomfort stems from an argument made by Frankfurt city planner Helmut Bosch. [12] In his view, the city’s primacy as a trading center—which dates back to the eleventh century—was enabled by the Franks’ complex association with its repressed Jewish minority. Historically, Jews in Europe were assigned those economic functions deemed unsavory by premodern Christians but deemed functionally essential by emergent capitalist societies. In other words, it is hard to imagine how Frankfurt could have become the significant medieval trading center that it was without the economic incentive provided by the institutionalization of interest-bearing loans based upon real collateral. It was these economic functions that were administered by Jews and that enabled the city’s sophisticated trade economy. This schizophrenic social relation between Franks and Jews was played out in alternate periods of persecution and tolerance.

It is well documented that Jews were minority residents in Frankfurt as early as the twelfth century. In 1349 the expanding Jewish population was assigned blame for an outbreak of the plague and mercilessly persecuted. A century later the traditional Jewish quarter near the cathedral was declared off-limits to Jews who were subsequently relocated en masse to a far smaller ghetto near the present-day Borneplatz known as the Judengasse, or Jew’s Alley. In 1500 there were some 200 Jewish inhabitants of the ghetto that rapidly grew by 1550 to be 1,000 of Frankfurt’s total population of 12,000.

By the seventeenth century Jewish bankers like Samson Wertheimer had secured the support of Emperor Charles VI by helping him to finance his military ambitions. The institutional relation of Jews to the emperor is best described as a condition of semifreedom in which imperial protection was granted as a condition of servitude to the imperial treasury. The rising visibility and aspirations of Jews, it is said, helped to provoke the peasant revolt of 1614 that again led to the plundering of the ghetto and to the expelling of Jews from the city. The emperor, however, intervened militarily on behalf of his bankers and forcefully repatriated Jews to Frankfurt in 1616. In this version of the story, Frankfurt became an independent Imperial city, not on account of the Christian guilds and burghers, but on account of the Jewish bankers.

In spite of such systemic persecution and devastating ghetto fires in 1711, 1721, and 1796 the Frankfurt Jewish community grew to be one of the most important centers of Jewish culture in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Europe. It was this legacy of Jewish industriousness, best exemplified by the career of Meyer Anschel Rothschild (1743–1812)—founder of the famous Rothschild Bank—that was responsible for much of Frankfurt’s nineteenth-century economic and cultural achievement. In 1811, Jews achieved citizenship, in 1864 full political equality, and by 1874 Frankfurt’s Jews had become so successful and assimilated that the community gradually dispersed into the city fabric. Both the University of Frankfurt, founded in 1914, and the famed Frankfurt Institute for Social Research, founded in 1923 by Hermann Weil, owe their existence to Jewish philanthropy. The simple statistics are these: in 1925, 55 percent of the Jewish population worked in banking, trade, inns, insurance, or transport, but less than 20 percent worked in craft and industry. In that same year 67 percent of all Frankfurt’s prosperous bankers were Jews. [13]

The modern period of Jewish success and assimilation, however, came to an official end on January 30, 1933 when the Nazis seized power. The Reichskristallnacht pogrom of November 9–10, 1938 set the stage for the systematic deportation of the city’s 30,000 Jewish citizens to the death camps. Approximately 100 persons survived.

This second interpretation of Frankfurt’s banking history inspired by planner Helmut Bosch is sobering, but also more satisfying than the popular account found in the press and in casual conversation. Bosch argues that Frankfurt’s contemporary banking industry, including its stock exchange, are not a postwar demonstration of rational invention by good Germans, but rather the direct heir of the Jewish coin-exchange that emerged in the city well before 1585. In Bosch’s view, Nazi anti-capitalist irrationality and intolerance temporarily destroyed Frankfurt’s long history of banking and cosmopolitan tolerance. [14] Without Nazi intervention, there would have been no banks in Düsseldorf to repatriate.

The point of briefly returning to this difficult history is not to reopen old wounds, but rather to better understand how Frankfurt has successfully recuperated its long tradition of banking and cosmopolitan tolerance. [15] The concentration of Europe’s postwar banking industry in Frankfurt was, then, not an act of invention, but an act of recuperation. This project was not one simply of reconstructing an industry dislocated by radical anti-Semitism and anti-capitalism, but a project of recuperating the cultural tolerance upon which banking and trade depend. Put simply, money knows no color. [16] The optimization of exchange demanded by capitalism depends upon the removal of those cultural barriers that would restrict cash flow to and from any quarter. In this sense, liberal capitalism is an inherently tolerant system. This observation is, however, hardly original. Marx and Engels observed in the Communist Manifesto, first published in 1848, that

. . . the bourgeoisie has through its exploitation of the world market given a cosmopolitan character to production and consumption in every country. . . . National one-sidedness and narrow-mindedness become more and more impossible, and from numerous national and local literatures, there arises a world literature. . . . [17]

One does not need to embrace the Communist Manifesto to argue that capitalism has tended to globalize local cultures and the environments they construct.

Both Marxists and capitalists commonly argue that architecture is the material embodiment of cultural politics. The patterns in which cities are constructed, the materials and technologies employed physically to build them, and how they appear to viewers is no accident of singular aesthetic whim. Rather, such constructions realize in material form the cultural conflicts of their time. In this sense, the construction and reconstruction of Frankfurt documents the struggle of Frankfurters to tolerate not just otherness, but the very idea of modernity itself. Planner Helmut Bosch alluded to this struggle in 1990 when he questioned if “this amount of modernity [referring to the proposed West End banking center] could live wall to wall with the historic substance of the city.” [18] Bosch was, of course, acutely aware of the previous postwar reconstruction of the “Römer”—the city’s medieval town hall—and the 1983 Disney-like simulation of the bombed-out half-timbered houses of Römerberg that sit across the square from the historic town hall. The expense that Frankfurters lavished upon these architectural reconstructions reflects the determination of some citizens to reconstruct the German society that existed before the war. Some would argue that these are examples of nostalgic, or even xenophobic architecture—an attempt to purify the compromised history of space. [19]

In his concern for the apparent modernity of the banking center plan, Bosch was equally aware of the even earlier public outrage that followed the construction of the brutalist-inspired Technisches Rathaus in Römerberg in the 1970s. It is not at all unreasonable to interpret these related architectural events as the public rejection of modern architecture and the social conditions presumably housed within it. Simply put, our argument here is that the reconstruction of the Römer and the recuperation of the banking center in new form are related events, or as Bosch would have it, “two sides of the same coin.” [20] On the one side is the intolerant and xenophobic rejection of modernity and on the other side is the tolerant embrace of those same conditions. This dialectic pair is, of course, particularly at home in Frankfurt, which is the home of the Institute for Social Research where dialectic critical theory emerged. [21]

It is important to recognize that as early as 1946 the city of Frankfurt erected a plaque at the Borneplatz to witness the destruction of its Jewish community. Nearly all German cities have, of course, made similar witness, but not as early as the citizens of Frankfurt. In 1966 a monument proposal by the Frankfurt architect J. Mayer helped to stimulate a subsequent memorial proposal by Paul Arnsberg. Arnsberg’s project was finally realized in 1987 as a permanent archaeological interpretation of the Judengasse when the war-demolished ghetto was redeveloped for other municipal purposes. Although many Germans disagree, Helmut Bosch argues that among German cities, Frankfurt is exceptional for coming to terms with its participation in National Socialism so early. In contrast, Berlin began the process of cultural recuperation only after the capital returned to the old Reichstag after national reunification.

In sum, the return of the banking industry to Frankfurt can now be interpreted not just as the stylistic victory of modern architecture or the recuperation of liberal capitalism, but as the recuperation of the rational tolerance upon which capitalist societies depend in order to function. It is this conceptual link to tolerance of cultural conflict that qualifies the juxtaposition of modern banks and faux half-timbered houses as an exemplar of liberal minimalism as defined by Barber. The next problem will be to examine how the liberal minimalist regime of Frankfurt has attempted to resolve, or balance the conflicting demands of economic development, environmental protection, and social equity depicted by Campbell. To do so it will be helpful to look at the particular case of the Commerzbank building because it serves as a principal symbol of economic globalization and the banking district to Frankfurters.

Part 3: The Commerzbank Tower as a Particular Case of Sustainable Development

By the early 1980s, the Commerzbank had expanded its staff to occupy some thirty locations throughout Frankfurt. [22] Such crowded and dispersed conditions were not atypical in the banking industry during that period. Planner Bosch reported that a survey by the City of Frankfurt Planning Office in the 1980s documented a huge pent-up demand for new banking office space. This unsatisfied demand reflected, of course, historical conflict with other interests—principally those of residents in the West End district adjacent to the traditional banking area. In the 1960s the West End was home to approximately 45,000 citizens who prized the district’s historic architecture, central location, and green backyards. Growing development pressure resulted, first, in the forced removal of many residents and, second, in the 1969 creation of Aktionsgemeinschaft Westend, a grass roots citizens’ initiative that actively fought commercial redevelopment of the district. Nicole Weidemann, a founding member of that group, was among those who systematically reported to the city illegal demolitions or conversions of apartments into office space. Weidemann and her colleagues also documented architectural conditions that met local criteria for historic preservation as a strategy to stall redevelopment on other grounds. [23] When the conflict over housing, now remembered as the Häuserkampf, degenerated into disruptive street violence, the radical activism of related activist groups such as “Revolutionärer Kampf,” the “Häuserrat,” and the “Putztruppe” was supported only by a few leftist members of the Social Democratic Party (SPD) majority of the city council. [24] There is, however, little doubt that such radical citizen activism made it strategically, if not tactically impossible, for growing banks to appropriate adjacent residential areas.

In the wake of the Häuserkampf of the 1970s there were by the mid-1980s two competing schemes to accommodate frustrated banking interests—one supported by the conservative Christian Democratic Union, or CDU, and the other by the more liberal SPD. The CDU favored a low-rise axial development scheme that would reinforce existing transport routes along the Mainzer Landstrasse. In hindsight planners have recognized that such low-rise development would have effectively suburbanized the city. The ironic rationale for this scheme was an explicit aversion to American-style high-rise density and the ecological devastation associated with American cities. Following the 1985 election, which was won by the CDU, Commerzbank reluctantly acquired property along the favored axis with the intent of consolidating its far-flung operations there. [25]

The second scheme to accommodate frustrated banking interests in Frankfurt was favored by the leadership of the liberal SPD. In 1987 the SPD leader, Martin Wentz, reluctantly argued that any future bank construction be concentrated in the old banking quarter as a means of reducing development pressure upon adjacent residential neighborhoods. This proposal stimulated intense debate within the SPD because of its implicit endorsement of “skyscrapers.” [26] It seems that rank and file members of both the conservative CDU and the liberal SPD shared a dim view of an Americanized urban landscape. This political debate, however, shifted to favor high-rise development after the election of 1989 in which a coalition of the SPD and the German Green Party prevailed. The so-called red-green coalition lasted from 1989 until 1995—these were the years of Commerzbank’s development.

In the era of the red-green coalition, Volker Hauff became the somewhat remarkable first choice for the Mayor. This choice was so interesting for our purposes here because Hauff—a former member of the Brundtland Commission—coauthored the first operable definition of “sustainable development.” Perhaps even more unlikely was the election of Daniel Cohn-Bendit as the leading Green Party representative in the Frankfurt City Council. Cohn-Bendit, a Frankfurt native, was a former student leader of the 1968 Sorbonne revolution in Paris. Under the leadership of these two progressive environmentalists, an explicit red-green agreement was reached that called for “. . . a policy of ecological and social responsibility.” In this negotiated political territory, the concept of the skyscraper began to take on new meaning. Skyscrapers first became associated with social responsibility because they avoided the displacement of traditional neighborhoods inhabited by an active and diverse population. Second, they became associated with environmental responsibility because skyscrapers avoided suburbanization and the aesthetic, logistical, and social blight that comes with sprawl. Such emergent political logic mandated that “. . . a sustainability review [be conducted] for every single [banking center] building project.” [27] Thus, third, skyscrapers became associated with environmental responsibility because they implied the use of advanced, energy-efficient technologies. Although few Frankfurters would argue that the skyscraper is an inherently sustainable architectural form, the public talk so valued by Barber seems to have led disparate groups to reconsider the meaning embodied in it.

It was into this political context that the international competition for the Commerzbank was thrown and it was out of this context that the competition was developed. In June 1990, the “Framework Plan Banking District” conducted by Novotny, Mähner, and Associates was released. The so-called “Novotny Study” recommended a building of 133 meters adjacent to the historic Kaiserplatz—the current site of the Commerzbank tower. In preparation for drafting the competition brief, Commerzbank did make application to the city planning department to demolish several historic structures that formed the perimeter of the block purchased for development. [28] That request, along with several other Commerzbank proposals, was heavily opposed by citizen initiatives and ultimately rejected. City Planner Bosch and the news media document that intense, detailed negotiations between the Commerzbank and the city lasted for several months. [29] At the end of this negotiation, the city and the bank agreed upon a program, or description of the building that satisfied the interests of those sitting at the table. The building would be a model of energy efficiency and environmental health. It would contain shops and a publicly accessible restaurant at street level, rather than an exclusive dining room on the fiftieth floor. A lecture hall would be made accessible for public programs at all hours. Parking would be reduced in favor of support to public transport. And not least important, the complex would include housing. In Bosch’s view, this was to be not a bank building but a mixed-use urban development project. [30] Nicole Weidemann, then chair of the ever-present citizen group, Aktionsgemeinschaft Westend, commented that the project program was “. . . no reason to rejoice, but [it is] a compromise we can live with.” [31] In effect, a formula for a new kind of tall building had been constructed.

Such significant economic and programmatic concessions on the part of a developer may seem remarkable to American readers. It would, however, be quite wrong to leave the reader with the impression that citizens and a powerful municipal authority had forced a reluctant Commerzbank to invest its capital in environmental protection measures. It is certainly true that left to its own judgement the bank would not have been so socially responsible with regard to public amenities. Indeed, it took “special encouragement” to obtain such concessions. [32] The employment of radically efficient environmental technology was, however, very much a part of the bank’s development strategy. By 1990, Commerzbank had already incorporated environmental issues into its corporate vision. [33] In the early 1990s, the bank created the senior post of Commissioner for the Environment (Umweltbeauftragter) who was charged with the greening of all bank operations. [34] Environmentally inspired programs included “environmental loans” to entities unable to obtain them elsewhere, philanthropic funding of the World Wildlife Fund and the Nationalpark Bayerischer Wald, and the creation of the Commerzbank/Impulse-Environmental Award for innovative enterprises.

At the beginning of the 1990s, environmental awareness was at its height in Germany. As a result, many have concluded that Commerzbank was simply “green-washing” its image in order to exploit public sentiment. The evidence, however, seems to suggest otherwise. An advisor to the Green Party leader Daniel Cohn-Bendit, for example, argued that “the idea to make the building green must have had its origins within the Commerzbank . . . [because city] policy didn’t have that much to say [about specific environmental control techniques or social objectives].” [35] Jürgen Braune, the Greenpeace activist, agreed that city ordinances left enough leeway to construct what could have been a very conventional building. [36] One must conclude, then, that individual bankers, as well as the corporation, were responsible for the environmental agenda that Sir Norman Foster was ultimately charged to realize. The competition brief can, then, be understood as a material proposal, or recipe for conflict resolution.

In response to the socially constructed competition brief, design proposals were submitted by invited firms on June 3, 1991. The competition jury, however, had difficulty in reaching a unanimous decision. The jury technical advisor, Otto Frei, recommended a run-off competition between the London office of Sir Norman Foster & Partners and the German architect, Christopher Ingenhoven. Commerzbank executives, however, refused to cooperate—as did Foster—and amid some controversy, Foster was selected by mandate of the bank. Although Ingenhoven’s proposal may have been the more technically advanced, beginning on June 29 the popular press described Foster’s “winning” design as an “ecological high-rise” [37] and an “ecoskyscraper.” [38] Martin Kohlhaussen, the spokesman of the Commerzbank Board of Directors, confirmed to the world that “. . . [i]t is all about ecology.” [39]

It is not within the political scope of this article to enumerate in detail the environmentally inspired technologies that were employed in the building. [40] The technologies incorporated into the final design include: so-called “double-leaf facades,” district heating, absorption chilling, hydronically cooled ceilings, lighting integrated with ventilation, nighttime thermal mass charging, and an energy management system that operates windows. These are exotically expensive technological choices by American standards. But perhaps the most spectacular aspect of the design is the naturally ventilated atrium and system of “sky-gardens” developed by Foster. That all workstations are no further than nine meters from an operable window, thus guaranteeing employees access to natural light and ventilation, is a feature that has captured the enthusiasm of the public. Although workspaces without natural light or natural ventilation are typical in American office buildings, they are actually illegal in Germany—a result of legislation initiated by strong office worker unions. In many respects, the constructed building does not just satisfy code requirements, it actually exceeds them. Architecture critics have argued that the design team’s manner of satisfying German environmental codes amounted to nothing less than the reinvention of the skyscraper as a building type. [41]

Dr. Arnheim Müller, Director of Development for Commerzbank, has documented that the energy performance of his building is 30 percent more efficient than buildings of the same type built in the same period—the Messeturm by Helmut Jahn, for example, was just completed when the Commerzbank was in early design stages. [42] Perhaps more significant, however, is the observation made by city planner Bosch. He argues that the public discourse that accompanied the development of the Commerzbank building has stimulated a new era of energy-efficient architecture in Frankfurt. [43] Although Bosch recognizes that the Commerzbank is a far more satisfying example of tectonic clarity than the projects that have followed it, he claims that more recent projects—the Maintower, for example—are actually more energy-efficient than the Commerzbank tower. Just as the banks vie for the highest tower and the most recognizable crown, they also vie to publish the lowest energy consumption rates in order to gain favor at city hall. In this limited sense, it is fair to argue that the Commerzbank building has become a material model for the public discourse of its time.

One can, then, describe the development of the Commerzbank tower as what Andrew Feenberg would characterize as a case of “subversive rationalization.” He means by this term that the very idea of what a tall building might be was redefined by years of public talk by Frankfurters concerning the desired qualities of urban life. The American model of a skyscraper was not simply redecorated with new architectural signs, or green-washed, but reconceived in local terms through the social construction of the new “technical codes.” [44]

Part 4: Analysis, or, Does the Empirical Evidence Support the Theoretical Model?

What can now be said about Frankfurt as a model of sustainable urban development? Campbell’s triangular model argues that the interests of economic development, environmental protection, and social equity must achieve a dynamic balance in order to meet his definition of that term. What follows can best be understood as a qualitative scorecard derived from the assessment of Frankfurters themselves.

Regarding economic development—demonstrating that the interests of economic development are served by the construction of banks is something of a tautology and needs little analysis. Frankfurt has not just recuperated its prewar national banking tradition, it has transformed it. The current banking industry is, however, neither limited to the national economy nor managed by Jews. Rather, the industry is transnational in scope and managed by a more diverse, but largely non-Jewish majority. In the summer of 2001, there were proposals under consideration by the City of Frankfurt and the European banking system to develop no fewer than six new towers in the traditional banking area and to redevelop the nearby railway yards of the Hauptbahnhof to accommodate global banking interests. These indicators certainly support the notion that the interests of economic development in Frankfurt are being well served indeed.

Regarding environmental protection—there are two views of Commerzbank’s environmental intentions. First is the skeptical view offered by Uli Baier (Green Party representative to the City Council), Barbara Holzhausen (Green Party official), and Käthe Schröder (architecture critic). They argue that public discourse in Germany regarding environmental protection was at its peak in the years leading up to the Novotny Report (1990). The subsequent period in which the Commerzbank tower was in its formal planning stage (1990–1994) was, in the view of these observers, strongly influenced by the bank’s desire to court public approval through a public relations campaign designed to represent the bank as a good environmental citizen—in other words, instrumentally to paint itself “green.” It is these same observers who tend to argue that a “sustainable high-rise” is an oxymoron by definition—meaning that any tall building is disproportionately resource consumptive and must result in an unhealthy microclimate. It is also these same observers who associate sustainable, or green architecture with more rural, or romantic conditions. Quite interestingly, the Commerzbank executive, Arnheim Müller, agrees that there can be no such thing as a “sustainable high-rise.” In his technocratic view, however, the rationale behind the project is not environmental protection so much as productive efficiency realized through reduced energy consumption and increased worker productivity. Although there has been no attempt at postoccupancy analysis to document increased worker efficiency, Commerzbank executives have discussed such a project with staff at Carnegie-Mellon University in Pittsburgh. Müller is indeed keenly interested in the possibility of rationalizing the bank’s investment in environmental quality as a form of indirect—and thus nontaxable—worker compensation. [45] The pessimistic view of Commerzbank’s environmental performance is, then, just that. Observers on both the inside and outside of development decisions view the project as architecturally accomplished, but ultimately an economically inspired experiment in energy efficiency and long-term cost reduction, not an experiment in environmental preservation. In this skeptical view environmentalism is only thinly veiled economic determinism.

In the optimistic view of environmental protection held by Jürgen Braune (Greenpeace activist) and Helmut Bosch (city planner), it is no longer appropriate to demonize corporations as evil capitalist institutions, nor their managers as distant profiteers. These optimists argue that there is a clear “red line” of cultural continuity from the political activism of 1968 to today. Although the radical ideals of that period have certainly mellowed with age, these observers argue that the same Frankfurt University students who occupied the barricades in 1968 now occupy both the board rooms of the Commerzbank and the halls of political power. [46] Daniel Cohn-Bendit is, perhaps, the best exemplar of this phenomenon. He has since had a distinguished career as a representative of the Green Party to the Frankfurt City Council, and subsequently, a German Representative of the Green Party to the European Parliament. According to Barbara Holzhausen, Cohn-Bendit publicly argued against any building greater than three-stories in height in the early 1980s, but by 1994 he became a principal champion of increasing the height of the Commerzbank tower to 185 meters. [47] Although there is no direct evidence to support a height for environmental technology or public amenity exchange there is at least its shadow.

Braune and Bosch are quick to distinguish the confrontational politics of the 1960s and 1970s from the more conversational, or cooperative politics of the twenty-first century—the latter is, in their view, far more productive. Braune and Bosch do not naively accept Commerzbank’s environmental intentions as disinterested—far from it—they appreciate the political nature of the lengthy negotiations in which environmental and social objectives have been realized by granting the bank significant economic concessions. [48] In the end, however, these sophisticated participants are willing to accept the environmental intentions of particular corporate managers as genuine.

The assessment of social equity is similar to that of environmental protection, there are two views: the skeptical and the optimistic. The skeptics—Barbara Holzhausen (Green Party), Käthe Schröder (architecture critic), and Nicole Weidemann (activist)—view the Commerzbank tower as the exclusive domain of elite corporate workers. Although the federal law mandates a two-step development process that includes public participation, the level of public participation was experienced by these actors as perfunctory rather than substantive. [49] Even within the Commerzbank hierarchy this view holds true. Arnheim Müller, for example, confirmed that bank employees had virtually no input into the project scope, program, or design. Such employee input would, he argued, have slowed the development process unacceptably. [50] So, yes, the bank has a restaurant open to the public, but it is architecturally isolated from the street because it was raised to the second level and is thus effectively private. On Saturday August 4, 2001, for example, there were three tourists in the café sipping coffee at 1 p.m. because there was no food being served on a day when few bank employees were in the building. At the same time, adjacent cafés on the Kaiserplatz were overflowing. Yes, there is housing included in the project, but 4,500 square meters, or 60–70 units, is a drop in the bucket compared to the number of units that were displaced by related commercial development in the neighborhood. [51] And, yes, there is an auditorium available for public use, but no one knows about its existence or how to book the facility. And, yes, Commerzbank workers have the benefit of architecturally splendid working conditions with natural ventilation and natural light, but these are elite executives who understand this environment to be a form of exclusive compensation that is not available to lower-level Commerzbank workers in other locales. In fact, recent Commerzbank office space constructed in Frankfurt for lower-level workers does not meet the same environmental and social standards. In this sense space in the Commerzbank complex is very hierarchical rather than equitable.

In the optimistic view of the social equity realized by the project, Commerzbank executive Arnheim Müller and city planner Helmut Bosch understand the tower as a first step toward realizing the compact city as a setting for the “new economy.” Both see such a high-quality office environment as a model for others to follow. Müller rationalizes the failure of Commerzbank consistently to employ the same environmental and social standards as “an unfortunate and temporary return to the dark ages.” [52] Beyond this agreement, however, the executive and the planner disagree. Based upon a description of other Commerzbank projects emerging in 2001, it is reasonable to argue that the bank does see its workers as an elite resource that requires protection from the “distractions” of the city. Müller, for example, envisions the development of exclusive trans-corporate enclaves of “knowledge- sharing,” where the every need of highly compensated workers would be satisfied on a 24/7 basis. In contrast, Helmut Bosch is optimistic about the ability of professional planners to negotiate exactly the opposite—mixed-use neighborhoods of diverse public and private space. Environmental activist, Jürgen Braune, voices a different kind of optimism. While he is skeptical of the power of government to do much at all, he is very optimistic about the prospects for NGOs to negotiate explicit social equity issues directly with corporations. The Greenpeace “Clean Construction” initiative is a case in point. This is a program where professional consultants retained by Greenpeace assist union construction workers affiliated with the IG Bau—Europe’s largest construction union—to inspect construction sites and thus reduce environmental and health hazards while increasing energy efficiency. [53]

Conclusion

After digesting the assessment of these skeptical and optimistic Frankfurters, we are left with a vivid, if not perfectly clear picture of the state of sustainable development in the city. Two principal conclusions can be reached: the first concerns the mechanisms of conflict resolution and the second concerns the mechanisms of economic determinism.

One cannot help but be impressed by the degree of conflict resolution achieved in the process of developing Frankfurt’s banking landscape. Although the articulation of differences in 1980—the height of the housing conflict—was distinct and powerful, by 2001 respondents from each interest group voiced only minor dissatisfactions. This may well be a sign that most interests were satisfied and that no principal interest was vanquished. It may also be a sign that weaker interests were suppressed. Of course, there were many less visible interests, such as Jews, bank employees, and dislocated renters that were never invited to participate in the discussion in the first place.

The representational function of the architecture, however, particularly of the Commerzbank tower, played no small role in the resolution of old conflicts. The authors found that even those citizens who were initially hostile to the concept of skyscrapers have grown to identify their own interests with them. The new Frankfurt skyline has become a collective source of pride because it distinguishes, through architectural form, the unique role of the city in the global economy. It is this representational, or aesthetic function of architecture that may approach, if not satisfy, Barber’s desire to “transform” social consciousness and get beyond the atomized quality of liberal-minimalist society. That Frankfurters articulate a new sense of collective identity materialized in tall buildings is a powerful critique of the Lockean version of liberal capitalism in which the whole of society is never more than the sum of its individual parts. Beauty has social consequences.

In all the data collected in Frankfurt, however, the views of skeptical Frankfurters tend to prevail—there is an underlying rationale that we can only describe as economic determinism. This term suggests that any concern for beauty, environmental preservation, or social equity is always already prefigured by what Helmut Bosch described as “economic calculus.” Benjamin Barber associates this phenomenon with liberal-minimalist regimes where, in his language, “economics precede politics.” He means by this comment that economic arguments always trump environmental or social equity arguments. Barber’s argument for Strong Democracy, of course, requires the reverse, that politics—the public talk that balances the interests of economics, the environment, and social equity—precede economics. [54] Economist James Galbraith makes a similar but more expansive point by arguing for the autonomy of different realms of life. The problem for Galbraith is that in liberal-minimalist regimes economic values have come to dominate not just the environment and the calculation of social equity, but the intellectual, artistic, and even religious realms of public life. [55] Such domination is clearly hegemonic in that it has come to be understood as natural even by those who suffer most.

The arguments against economic determinism made by Barber and Galbraith are, however, not new. Marx and Engels made a similar critique of American capitalism in the nineteenth century. Although their critique may overstate the conditions found in contemporary Frankfurt, the globalization of American-style capitalism justifies their claim that liberalism in general

... has left remaining no other nexus between man and man than naked self-interest, than callous “cash payment.” It has drowned the most heavenly ecstasies of religious fervor, of chivalrous enthusiasm, of philistine sentimentalism, in the icy water of egotistical calculation. It has resolved personal worth into exchange value, and in place of the numberless indefeasible chartered freedoms, has set up that single unconscionable freedom—Free Trade. . . . The bourgeoisie has stripped of its halo every occupation hitherto honored and looked up to with revered awe. It has converted the physician, the lawyer, the priest, the poet, the man of science, into its paid wage laborers. [56]

Following this historic objection of progressives, then, any critique of Frankfurt, and of the model of sustainable development offered up by liberal minimalists there, must be based upon the imbalance imposed upon the triangulated model of sustainability by the economically deterministic logic of liberal capitalism. This almost banal finding will come as no surprise to most readers, yet its implications are no less significant. If the interests of economic development always prefigure the value found in the remaining two points of the triangle one can never end up in the center.

Political conditions in Germany, however, provide some reason for optimism. Planner Bosch argues that the German constitution and the federal planning law have already at their disposal mechanisms intended to balance the demands of commonweal and private property. The concept of Abwägung, or “weighing up,” gives planners the authority to tip the scales, if you will, in favor of those interests that are less forcefully represented, but considered valuable to community life. The only question, then, is if cities choose to employ the balancing tools that are constitutionally available. In common practice architects, planners, and citizens can only hope that the emerging discipline of environmental accounting, or consumer demand for green products, will adequately rationalize any investment in environmental or social health. Although liberal capitalism of the minimalist variety has clearly succeeded in institutionalizing tolerance as a condition of modern life, it has done so—as Galbraith has argued—at the cost of every other sphere of life. The hope of activists such as Bosch is that the concept of Abwägung, or weighing up, will guide future public discourse away from the logic and practice of economic determinism that has dominated the first fifty years of development in the new German nation.

Just as theory should inform practice, so practice should inform theory. In the empirical test of the triangular model of sustainable development conducted by the authors in Frankfurt, the geometry has come out distorted—the triangle is not an equilateral one. This finding suggests that Frankfurt is not yet a sustainable city, or that the “planner’s triangle” may itself require renovation. Two possibilities exist for continued development of the triangular model. The first is to develop it further as a quantitative measuring device for equalizing measurable conflicting interests. In this project, the triangular model remains within Lockean assumptions that citizens want nothing more than security and privacy. This will be a project for economists who embrace liberal-minimalist values. The second possibility, however, suggests that Campbell’s model might be understood as a qualitative metaphor for the dynamic and equilateral integrity of civic life. In this project, it might be developed as an action plan for sustainable and strongly democratic cities. This will be a project for citizens.